|

|

Post by victoriousscarf on Nov 6, 2010 19:40:56 GMT -8

Because, seriously, I'm a historian, this is what I do with my time. This will be updated pretty randomly as I find out more random things that might be relevant to anyone, might not be. Feel free to add anything you find as well.

An Incomplete Bibliography

Allen, Frederick Lewis. Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s (Perennial Classics, 2000) Originally Published 1931.

Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. (Penguin Books, 2005).

Behr, Edward. Prohibition: Thirteen Years that Changed America. (New York; Arcade Publishing, 1996).

Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World 1890-1940. (Basic Books, 1994).

Johnson, Nelson. Boardwalk Empire: The Birth, High Times, and Corruption of Atlantic City. (Medford Press, 2009).

McBride, Tom and Ron Nief. The Mindset Lists of American History: From Typewriters to Text Messages What Ten Generations of Americans Think is Normal. (John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2011).

Mowry, George E., Ed. The Twenties: Fords, Flappers & Fanatics. (A Spectrum Book, 1963).

Okrent, Daniel. Last Call: the Rise and Fall of Prohibition. (New York; Scribner, 2010).

Showalter, Elaine, Ed. These Modern Women: Autobiographical Essays from the Twenties. (The Feminist Press, 1978).

Ward, Geoffrey C., and Ken Burns. Jazz: A History of America's Music. (Aflred A. Knopf, 2005).

Yapp, Nick. The Hulton Getty Picture Collection: 1920s. Decades of the Twentieth Century. (Konemann, 1998).

Elsewhere in Europe for the Twenties

Gay, Peter. Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider. (New York; Harper Torchbooks, 1968).

Graves, Robert, and Alan Hodge. The Long Weekend: A Social History of Great Britain 1918-1939. (New York; W.W.Norton & Company Inc, 1963).

Weitz, Eric D. Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy. (Princeton University Press, 2007).

|

|

|

|

Post by victoriousscarf on Dec 11, 2010 22:42:17 GMT -8

|

|

|

|

Post by victoriousscarf on Dec 22, 2010 23:46:15 GMT -8

|

|

|

|

Post by victoriousscarf on Jan 28, 2011 22:06:04 GMT -8

Evolution of the Insanity PleaSo, not entirely 1920s related, but three guesses as to which character this might come up about? Also, just interesting law tidbits that are relevant to the period in between the 1920s. And I like sharing research.

|

|

|

|

Post by victoriousscarf on Mar 9, 2011 19:48:34 GMT -8

Alright, so since some characters are making this relevant: Pulled off HERE |

|

|

|

Post by victoriousscarf on Mar 21, 2011 10:41:01 GMT -8

Alright, so let's talk hobbies a little bit.

The first crossword books (So far as I can get out of this article) were published in April 1924 and took off like crazy, so by 1925 there were all sorts of crossword books, such as scriptural themed ones and, I'm not kidding guys, yiddish ones. ((Which means yes, they were not around in 1919. Whoops.))

Another thing that was very popular was Mahjong, and though the craze for it had ended by 1925, it was still a hugely popular game and could be found in different places. Which means, the Palace probably has a Mahjong area, and some of your characters will either have liked the game, or possibly still play it.

And of course dancing. But everyone should have known that one already.

|

|

|

|

Post by victoriousscarf on Apr 11, 2011 11:45:38 GMT -8

Guess what kits? It’s info dumping time.

Alright, so something we haven’t addressed in the board at all yet, though that’s relevant is the 1918(ish) Spanish Influenza epidemic that swept the world at the end of the First World War. The reason this is going to be very relevant in some ways for our characters 6-7 years later is that it killed 5 percent of the world’s population. FIVE PERCENT GUYS. Up to as much as 8-10 percent of young adults. And that’s the age group that most of our character’s belong to, which means this was something that would have affected them a whole hell of a lot.

However, when WWI was also killing plenty of people, and certainly affected the USA in 1917 and 1918 especially ((Remember: The USA only entered the war in 1917 and honestly, it was young recruits drawn up then, the draft was really young)) unlike WWI, the epidemic is not mentioned in most/any of the literature of the time. ((Sure, plenty of authors would deny WWI had anything to do with their writing, such as T S Elliot himself and Tolkien, but really, who here has read their work and believes that?)) Thus, even though the influenza was killing a lot of people, it gets talked about a whole lot less.

So let’s talk about what happened.

In terms of sheer numbers, the Influenza pandemic of this time killed more people than the Black Plague ((In fact, as a side note, many people when confronted with the Influenza thought it was the plague come back, and since the government was being shit with getting information out, it seemed entirely possible. To this day, in Australia in particular kids who survived it still think what they experienced was the plague.))

A lot of doctors were trained between 1870 and 1914 outside of the USA—so a lot of doctors who survived the pandemic who are running around now most likely might have been trained in Germany or the like. Also, almost anyone could claim the title of Doctor or Professor without actually having the qualifications. The first cure for a disease was discovered in 1891. The germ theory was also out and about during this time.

The Red Cross exploded during the war, and from 107 local chapters before the war to 3,864 at the end. 8 percent of the entire population of the United States worked at these chapters during the war. At colleges, when the USA entered the war, teaching of academic classes stopped to be replaced by military classes.

Now, it’s believed the Spanish Influenza originated in the United States, and moved over in a mild form to the European Front, where it certainly made many fall sick ((Ludendorff would attempt to blame the flu for why his last push failed)) but it was not quite as deadly, and when it turned deadly, many who had caught it in Europe would have a level of immunity for surviving the first wave. Which is not to say it wasn’t deadly at this time, just not in the way it would become.

The second wave came back to the United States in fall of 1918, when the war was still going on. September 3rd and 4th are dates where civilians began being admitted to the hospital for influenza symptoms. Military Camps, with many young men crammed together in not enough space, became some of the worst areas struck by the influenza, and military troop movements were what spread the disease originally. Port cities on the East Coast were struck first, and the hardest in September and October of 1918. Which means, in all likelihood Felidae was included along with Boston, New York, and Philadelphia as not only the first hit, but the hardest hit.

Alright, nightmare fuel is coming up here:

The influenza closed down cities. People who were fine in the morning would be struck down and dead 12 hours later. One doctor remarked that on his morning rounds, ever patient in the critical ward had died over night—every one of them, every night while this was going on. This disease caused bleeding out of openings, including nose, mouth, eyes and sometimes ears. So many were dying, that coffins became a closely guarded commodity, and shortly after the disease hit, many cities ran out of coffins in which to burry people. Families would have to dig their own graves for dead family members, and at a certain point a lot of cities pulled out steam shovels to create mass graves since undertakers could hardly keep up. Morgues were piled with bodies in the hallways.

Though the military was hit hard, 15 times as many civilians died. The disease came in waves, usually lasting 6 to 8 weeks in each city as it would peak and then drop off abruptly, but it moved in waves around the country, and just when a city thought they were safe, another wave hit. Though, each wave that lasted into the 20s that hit was less violent than the ones preceding it.

On September 26th the military cancelled the next draft, and wouldn’t call up another before the end of the war. The army did however, continue transporting troops to France—which took the influenza back with them. These ships basically became floating coffins.

Nurses were even harder to find during this time than doctors, and though there were many calls for volunteers, most people were too afraid to come out. Police were sent out at a certain point to remove dead bodies from family homes, as often times they had remained there, decomposing, for several days as the families often times were too terrified to move them. Six supplementary morgues were opened in Philadelphia. Priests were also sent to retrieve bodies with the police—and many of them caught the disease and died as well.

One day in October killed 759 people in Philadelphia alone.

By November though, the worst wave—the second wave, was over. The third wave would be terrible as well when it came in December and January. In some of the places not struck as badly as the second wave, it was worse this time through, but better in the areas hit the worst in the first wave.

February 1920 was also bad with 11,000 deaths in New York and Chicago in eight weeks.

So, to summarize: during the fall of 1918, cities were closed down completely. Few people would go out on the streets, churches and schools and any public gatherings were shut down and/or banned, and community life all but stopped completely. Surgical masks were seen everywhere but the streets were mostly empty. People were falling sick and dying in abrupt ways, looking fine in the morning and dead by that evening. If a person died at home, their body often stayed there for days as the family was terrified to move it, and there was a breakdown of public services. Dead bodies were being piled on top of each other in the hospitals and morgues, and this disease not only killed abruptly, but many of the patients bled as well, creating even more of a mess. There were not enough nurses or doctors even if one managed to end up in a hospital, so things like clean sheets were a dream.

Unlike the plague however, the disease did not kill everyone who got it, and many survived becoming sick… and many did not.

Now, as a historian I tend to like using more than one source, but few things are actually written about this incident in history, thus all of this was culled from John M. Barry’s The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (Penguin Books, 2005).

So, who’s suddenly tempted to go back and rewrite some history and/or fears sections?

|

|

|

|

Post by victoriousscarf on Apr 13, 2011 21:21:01 GMT -8

Alright, after that... pretty depressing last post, let's talk a little about fashion. Yes, everyone knows about the flappers, and I will ask Meadow at some point to expand these things, but fashion is very relevant for your characters. Men are pretty straight forward I will admit. However, be aware they're probably in suits, and that all men--all men, all all all--wore hats out in public. Even working class men would wear hats, though they would be newsboy caps usually and things like that. Flatter caps. The Fedora, if I'm recalling correctly, was pretty middle class. If you weren't wearing a hat in public, it was very rude. So, be aware of that if you're character goes hatless. ((As an interesting aside, men's lapels during this time were narrower than they generally are today. A large part of this comes from fabric rationing introduced in 1917 when Wilson went WAY overboard prepping for the war, so that pockets became shallower and lapels thinner)). Now, women's fashion is more complicated. They also usually wore a hat, and while men might take them off while inside, women didn't generally in public. But everyone wore hats. Women's waists were also pretty low during this time period and skirts were somewhat high. So, I know not everyone is as excited as fashion as I am, but some resources (more will pop up later) include: OMG THAT DRESS A blog of all fashion periods, but some great 1920s stuff. ((Also, Helpfully included tips for finding clothing from a specific time and place)) Metropolitan museum of art. Which is linked to a basic search for the 1920s, but there's plenty of other clothes from the 20s around if you search around a bit. More will come when I'm more functional. |

|

|

|

Post by kragjorgensen on Apr 17, 2011 22:33:37 GMT -8

(my main problem is that you copy-pasted availablility grades, which I have no idea about and made up) Alright, Ladies and Gentlemen. Welcome to Guns of the 1920's: Reloaded, I'm your host Kragjorgensen and I am about to tell you all more than you ever wanted to know about Guns in the Gangster Era. This list is by no means comprehensive. General rule of thumb: Many weapons were named for the date they were introduced. If the weapon is something like the M1917, it was introduced in 1917 and is fair game. In this episode, We will look at several American Service Rifles: Krag-Jorgensen [Picture]Cartridge: .30-40 Krag Capacity: 5 + 1 in the chamber Designed by Erik Jorgensen and Johannes Krag, the M1892 was the first multi-shot rifle to be officially adopted by the US Army. The weapon was reliable, accurate and operated smoothly, but it was loaded one round at a time rather than with chargers like the Mauser. Loading was often difficult in the heat of battle. After the Spanish-American War the Krag was phased out in favor of the Mauser-derived M1903. Springfield 1903 [Picture]Cartridge: .30-03, .30-06 Capacity: 5 Drawing from lessons learned in the Spanish-American War, the United States was looking to replace its obsolete Krag Rifles. Using features of the Krag and from captured Spanish Mausers, the United States produced a new weapon. The weapon borrowed so many features from the German design that the Mauser Company successfully sued the US Government for patent infringement. At the outset of the Great War, the Springfield was issued in its full capacity, especially to the US Marines. M1917 Enfield [Picture]Cartridge: .30-06 Capacity: 5 With America’s entrance into the Great War, the US government found itself in desperate need of weapons. There were not enough 1903’s to arm the thousands of men who were going to fight. Rather than re-tool the factories to produce the 1903, it was simpler to modify machines that were making P14 rifles for the British. These new weapons were produced and issued in greater quantities than the more famous 1903. |

|

|

|

Post by victoriousscarf on Apr 18, 2011 13:18:29 GMT -8

|

|

|

|

Post by kragjorgensen on Apr 20, 2011 19:13:35 GMT -8

Welcome to another episode of Guns of the 1920's: Reloaded, I'm your host Kragjorgensen and I am about to tell you even more than you ever wanted to know about Guns in the Gangster Era. Today's Episode: Shotguns. Double Barrel Shotgun [Picture]Caliber: Various Capacity: 2 Double-barreled shotguns have been around for quite a while and have remained relatively unchanged since 1875. They were made by a variety of manufacturers and a variety of style. They were easy to make, very easy to use, simple to take care of, and generally good for a variety of situations. Winchester Model 1887 [Picture]Caliber: 10 gauge, 12 gauge Capacity: 5 The first commercially successful repeating shotgun produced. The weapon was designed by John Browning by scaling and slightly modifying his previous lever-action designs. Winchester actually requested that he stop working on his pump-action design (which later became the Model 1893) to design this lever-action weapon. Relatively uncommon, it fell out of popularity with the introduction of readily available pump-action shotguns during the late 1890’s. Winchester Model 1893/1897 [Picture]Caliber: 12 gauge, 16 gauge Capacity: 5 + 1 in the chamber Designed by John Browning, it was one of the first successful pump-action shotguns. It was used by the Doughboys in the trenches of the Great War, where it was so effective that the Germans lodged a complaint that it violated the laws of war. The weapon did not have a trigger disconnect, which meant that the shooter could hold down the trigger and work the action, firing every time the pump was worked. Remington Model 17 [Picture]Caliber: 20 gauge Capacity: 5 + 1 in the chamber Yet another Browning design, the Model 17 was slated to be produced in 1917, but with the outbreak of the Great War, Remington was unable to manufacture it until 1921. While not popular, it was the basis for later models like the Ithaca 37 and Remington Model 31. Winchester Model 1912 [Picture]Caliber: 12 gauge, 16 gauge, 20 gauge Capacity: 5 + 1 in the chamber Designed by Thomas Crosley Johnson and partially based on Browning’s Model 1897, the Winchester Model 1912 was a hammerless shotgun that served alongside the Model 1897 in the Great War. Like the 1897 it also lacked a trigger disconnect, meaning that it could be fired multiple times by holding the trigger down and pumping the action. Browning Auto-5 [Picture]Caliber: Various Capacity: 4 + 1 in the chamber The first practical semi-automatic shotgun design ever mass produced and considered by John Browning to be his greatest achievement. The weapon gave its firer the ability to quickly fire more than two shots in rapid succession, with just the pull of a trigger. |

|

|

|

Post by victoriousscarf on May 1, 2011 20:55:08 GMT -8

|

|

|

|

Post by kragjorgensen on May 4, 2011 22:36:51 GMT -8

Welcome to another episode of Guns of the 1920's: Reloaded, I'm your host Kragjorgensen and I am about to tell you even more than you ever wanted to know about Guns in the Gangster Era. Today's Episode: Service Rifles Part 2 Lee-Enfield SMLE [Picture]Cartridge: .303 British Capacity: 10 Derived from the Lee-Metford rifles, the Lee-Enfield was first introduced in 1895. The weapon was the standard issue rifle for the British Army during the Boer war. It was slated to be replaced by the Mauser-derived P14, but the Great War broke out before full production could take place. The SMLE had a larger magazine capacity during the Great War and also had a cock on closing feature, which facilitated rapid fire. British riflemen were trained in the “mad minute” which was 60 seconds of rapid, aimed fire. Germans who faced this often thought they were being fired upon by machine guns. Pattern 1914 Enfield [Picture]Cartridge: .303 British Capacity: 5 After facing Mausers during the Boer War the British started working on their own version of the action, finding its range and power desirable. However, the Great War broke out before full production could commence. The SMLE remained the standard British army rifle; the P14 however was issued in a smaller capacity, especially as a sniper rifle. Due to lack of spare industrial capacity, Britain contracted with the US companies Winchester, Remington, and Eddystone to produce these weapons. The P14 was the basis for the 1917 Enfield. Ross Rifle [Picture]Cartridge: .303 British, .280 Ross Capacity: 5 Designed by the British eccentric Charles Ross, the Ross rifle was used by Canada in the early parts of the Great War. The Ross action was unique among bolt-action rifles of the time. While the majority of bolt-actions required the firer to rotate the bolt a quarter-turn before pulling it back, the Ross eliminated this step, producing what is known as a straight-pull. The weapon was very accurate and could theoretically be fired faster than a conventional bolt-action. However, it was sensitive to the dirty conditions of the Great War; it was phased out of front line usage in favor of the Lee-Enfield. Due to its accuracy, the Ross was retained as a sniper weapon and was the basis for a fairly successful series of sporting guns. |

|

|

|

Post by victoriousscarf on May 11, 2011 11:26:20 GMT -8

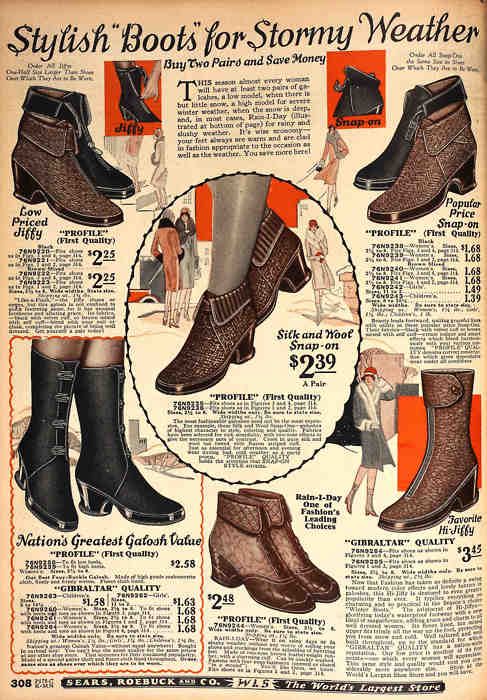

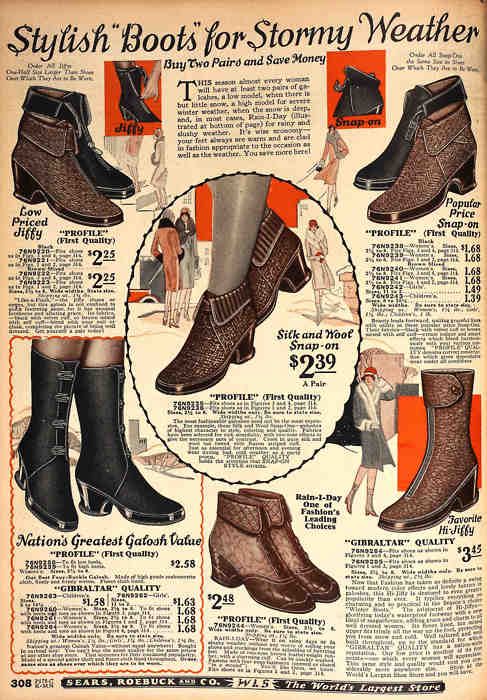

A page of winter boots from the Fall-Winter 1928 Sears Catalog. These boots all have hollow rubber heels and are meant to be worn over your shoes. |

|

|

|

Post by victoriousscarf on May 11, 2011 11:31:10 GMT -8

A good fashion blog in general, Ye Olde Fashion has some great 1920s objects, including a bathing suit and a lot of shoes. Link is to the 1920s tag. |

|